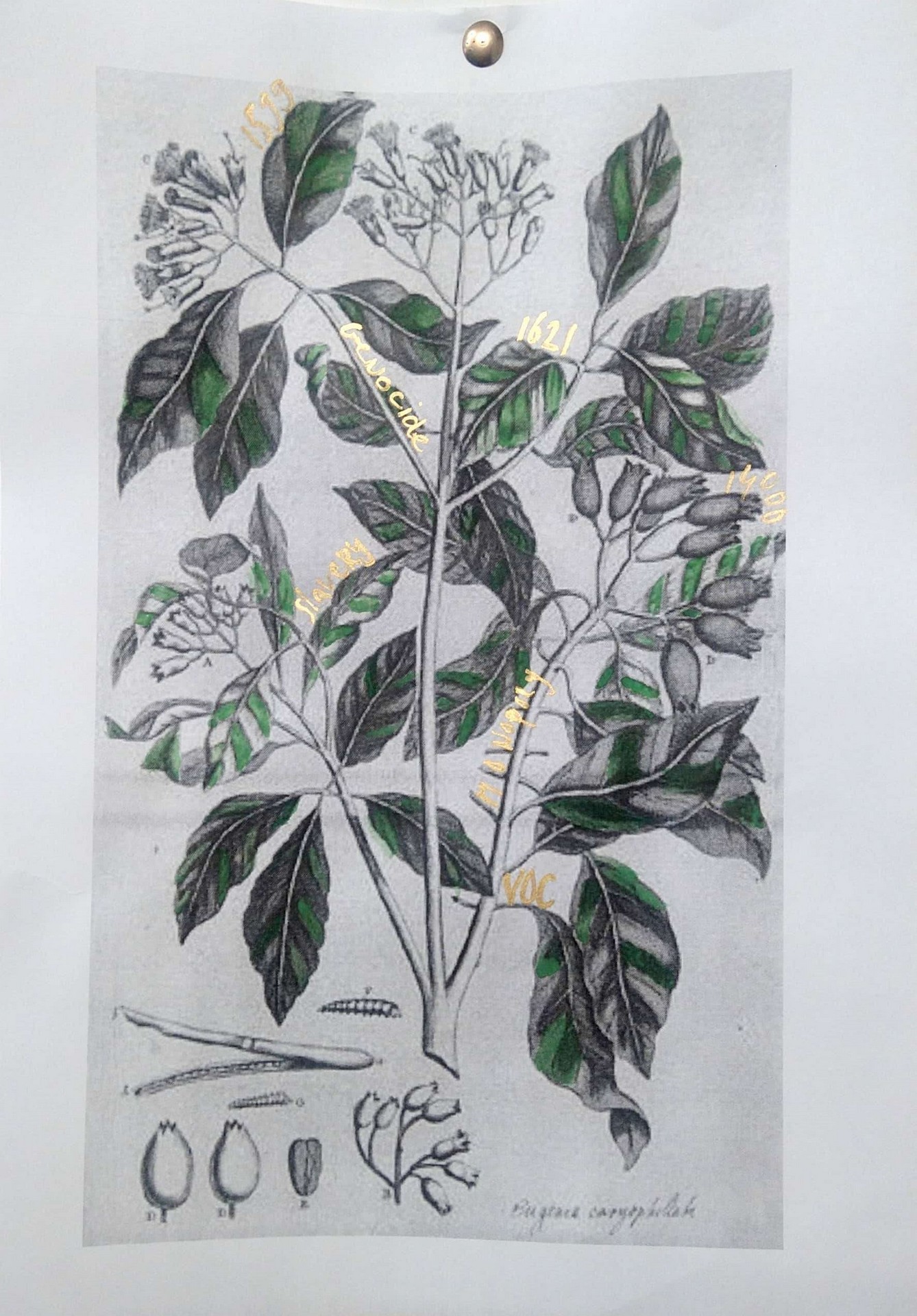

"Spice trade" (2023)

Spice trade

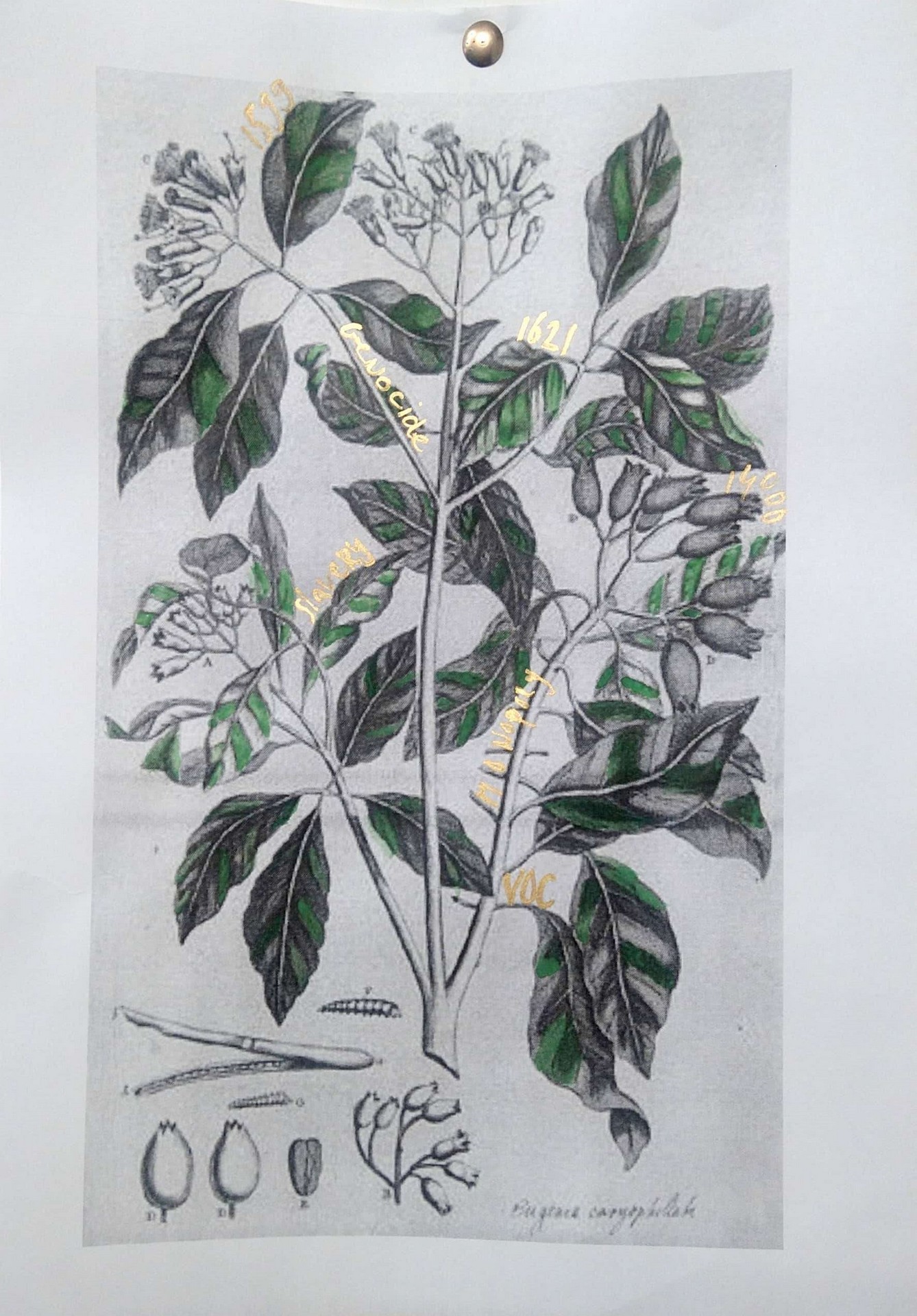

consists of two works. The first is a historic botanical print of a nutmeg

plant. In between the leaves, we see words written in gold that reflect the

violence that were committed in the name of the spice trade. Whilst colonialism

is an incredibly violent system, in Dutch discourse, it is often reduced to

mere trade relations. Adding to this, is the praise of all the amazing spices

that the Netherlands gained access to through this trade. This hides the

violence that is entrenched in this practice.

Firstly, to gain a monopoly on nutmeg, Dutch colonisers came to the islands

Banda in 1599 which at the time was the only place in the world where nutmeg

grew. To gain exclusive access to the spice, in 1621 the Dutch committed

genocide against the Bandanese inhabitants (Manuhutu, 2022). The Northern

Maritime Museum estimates 14.000 Bandanese inhabitants were murdered, forced to

flee, or enslaved to work at the nutmeg plantations (Northern Maritime Museum,

2023).

This piece aims to disrupt the innocence around the spice trade narrative.

While at first it seems like an innocent painting, looking at the text in it,

highlights the violence that is hidden behind the leaves. Whilst the botanical

piece might hide the harm between the leaves, the second part extracts the harm

and places it on a black canvas – now the words are highlighted and cannot be

ignored anymore.

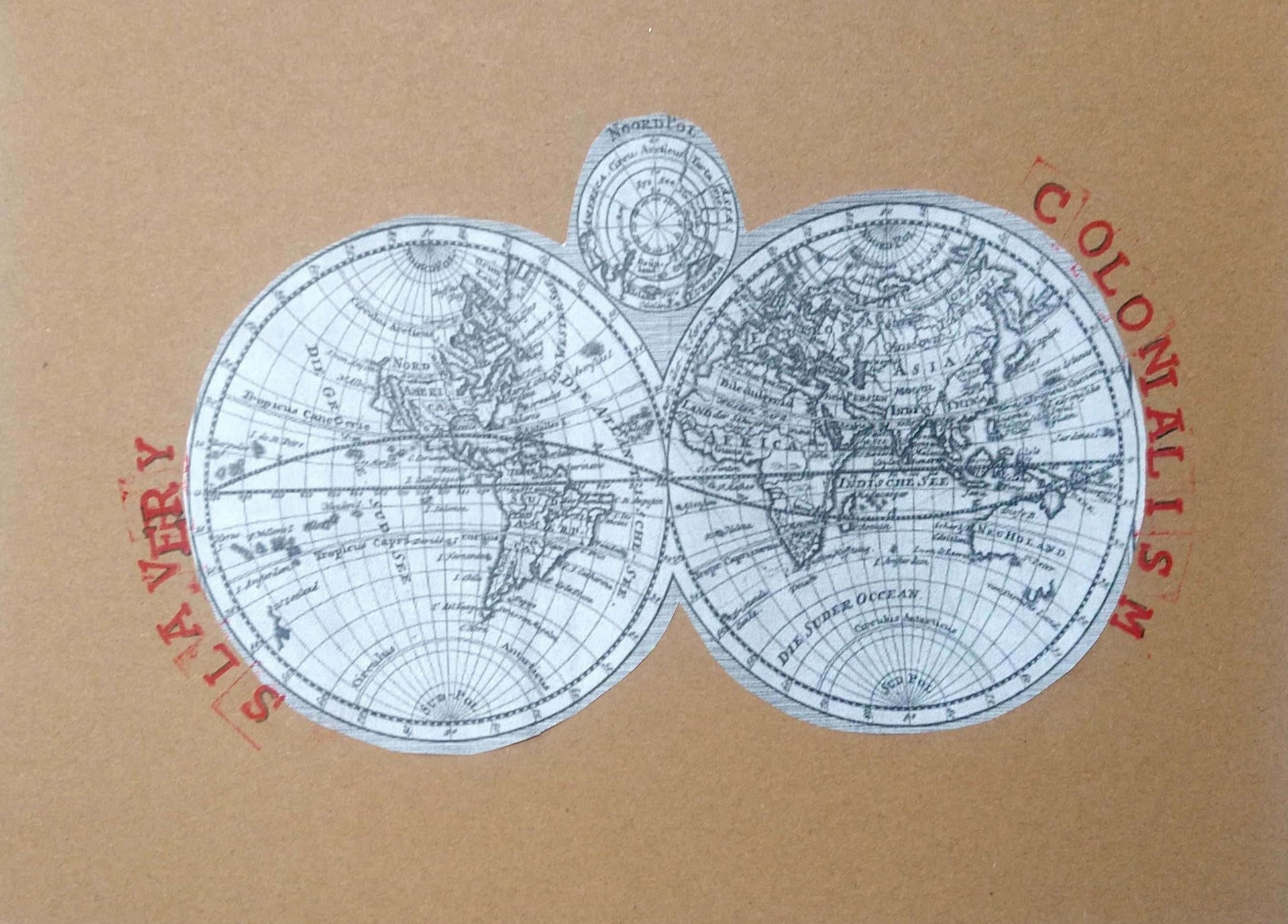

The other

set of works further disrupts this innocent spice trade myth. It portrays a

gun, taken from the painting ‘De slachting door de Hollanders op Banda in 1621’

(The slaughter by the Dutch on Banda in 1621) from the Museum of Banda, Rumah

Budaya (Manuhutu, 2022). The painting depicts the brutal genocide committed. By

taking the gun from the painting and decorating it with spices, it

re-emphasises the link between the violence committed and the objective to

monopolise the spice trade. While many of these spices are staples in the

average Dutch kitchen, it is collectively forgotten how access was gained to

them.

As such,

the related piece screams ‘Was it worth it?’ written in spices. It is placed

above a painting of the conquest of Jakarta. This work also emphasises and

reasserts the harm that is perpetrated in the name of the ‘spice trade’.

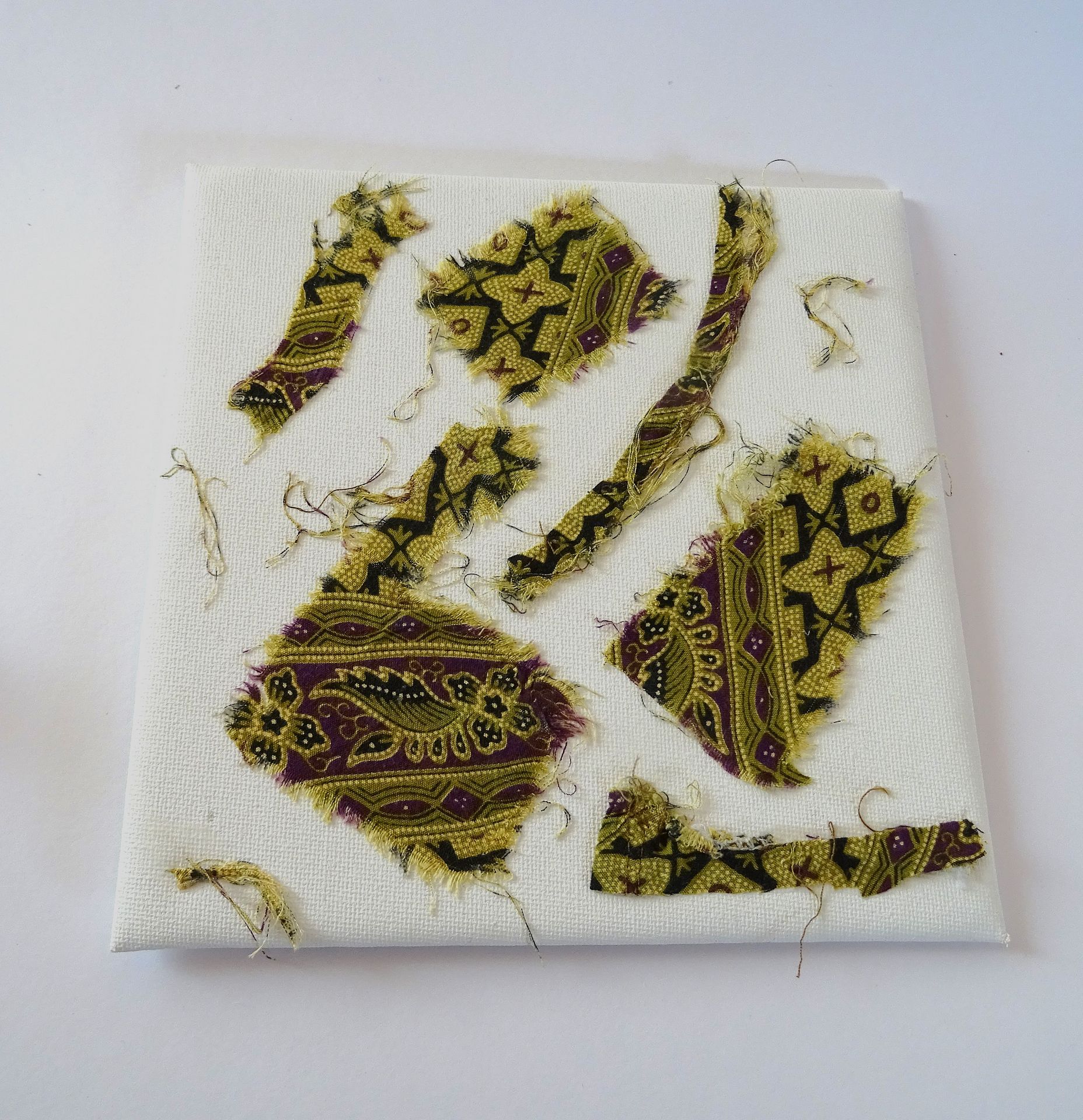

The pieces

aim to disrupt the colonial amnesia and selective memory about what colonialism

was. Instead, it acknowledges the violence of the system, of which we find the

legacy in our kitchens.